by Nathania Azalia

31 July 2025

In the face of the changing climate and rising energy demands, ASEAN is working towards a transition to cleaner energy. Central to this transition is a growing emphasis on making sure it is just and inclusive, to ensure that no one is left behind in the process. The principles of ‘just and inclusive’ advocate for a people-centred energy transition by protecting and empowering the ASEAN people in the shift from a fossil fuel economy to a low carbon energy system. However, a common understanding under these principles should be determined, including the matter of gender equality, to establish more inclusive policies and action plans. Despite regional efforts to promote equality, women still make up only 8% of the energy workforce in ASEAN. This gap is not just a number, it’s a reflection of deeper, intersecting barriers related to labour participation, education access, and leadership opportunities. These social dynamics, often shaped by longstanding cultural norms and systemic inequalities, are at the heart of the region’s gender imbalance in energy.

The concept of Intersectionality helps explain why the gender gap persist. It refers to how different social factors, such as gender, class, education and cultural norms, interact to create unique forms of disadvantage. In this case, it is about how issues such as employment, education, and decision-making processes interact to create gender inequality in the access to the energy sector. For example, the term ‘male-preferred’ territory exists within the energy sector due to factors like gender norms and limited access to opportunities for women’s participation, creating significant gap for men and women participation. Recognising the root causes of gender disparities and how they interact through the aspect of intersectionality is crucial to understand the energy-gender gap. Furthermore, providing an intersectional gender perspective in the journey towards a just and inclusive energy transition is vital to be applied to align with regional initiatives, especially the ASEAN’s energy blueprint – ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation 2026-2030 under the theme “Advancing Regional Cooperation in Ensuring Energy Security and Accelerating Decarbonisation for a Just and Inclusive Energy Transition”. Thus, this article identifies how social aspects including labour, education, and leadership opportunities have been influencing the state of gender equality in ASEAN’s energy sector and how the region can bridge this gap.

In a global perspective, women are often responsible with household and caregiving duties, which are often unrecognised, unrewarded, and unpaid. In ASEAN countries, women’s participation in paid labour is persistently low, with the narrowest gender gap in Lao PDR at 3% and the widest gap in Myanmar at 29.88%. Among employed women, many of them work in the informal sector, especially those in rural areas. According to the ASEAN Committee on Women (ACW) Work Plan 2021-2025, women make up only 45% of workers in Southeast Asia, and most of them are working in low-skilled, low-paid, and informal jobs with limited social security and employment benefits. Under the ASEAN energy sector, only 8% of women are employed in the industry, highlighting the disproportionate gender ratio. In extend, the label of household-and-caregiving expert for women is also shown in the energy sector, where they often serve as the ‘energy managers’ in the household, dealing with the payment of electricity, water, choosing more efficient and affordable cookstoves, where limited technical skills are required to complete the tasks.

Furthermore, high-paying formal jobs, including those in the energy sector, typically require science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) skills. Jobs in STEM are stereotyped as masculine, creating internalised gender bias in women’s interest to take on jobs in the field. There is an implicit perception that men would be more successful in STEM sectors and that women lack the technical capabilities. Moreover, women in male-dominated workplace tend to experience discrimination, and the persisting gender bias leads to discomfort for women working in non-traditional jobs. Unpaid work further influences this disparity, as women employers often view these responsibilities as a disadvantage. Unfortunately, the existing label could also be explained by the patriarchal culture dictating traditional gender roles, reinforcing the idea that household and caregiving duties are primarily a woman’s duty. This stigma is keeping women out from various economic opportunities, higher-paying jobs, and political decision-making processes, in issues such as energy, that would greatly impact their livelihoods.

Moving beyond economic inequality, women still face barriers in accessing qualified education and skill development, preventing them from entering formal high-paying sectors and leadership roles, especially in the energy sector. Again, patriarchal norms also influence educational systems, creating gender bias. This includes skills attainment and the reinforcement that contribute to the view and being viewed as lesser-than man in educational system.

A comparative study done in Indonesia, Malaysia, and several South Asian countries also found that government-issued school textbooks contain gender bias, such as mostly showing men in prestigious jobs and women working in domestic labour, showing a systematic underrepresentation of women. It also led to a strong belief that men were more inclined and “natural” in mathematics than women, discouraging women from taking STEM subjects such as engineering for higher studies. On average, only 19.3% of women graduated with a STEM degree in ASEAN, of which often pursue pharmacy, medicine, and biology as opposed to energy-related pipelines such as physics and engineering. The choosing of these subjects is related to the social norms that channel women into careers that are extensions of their domestic responsibilities of caregiving.

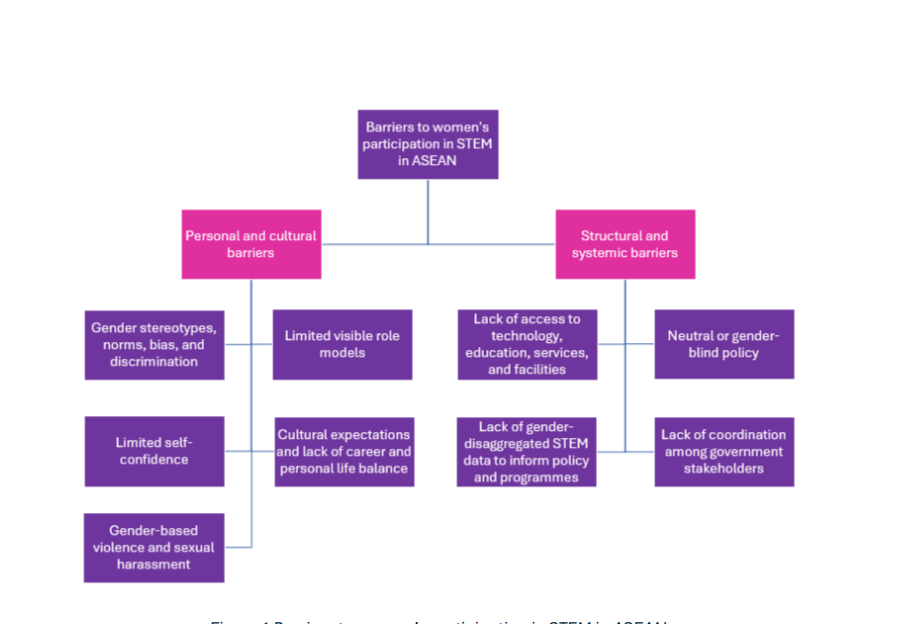

Although the number of girls who complete schooling at all levels of education is higher than boys in the ASEAN region, many young women struggle to access the job market and secure formal jobs, including in the energy sector, which typically require STEM skills. The existing barriers to ASEAN women’s participation in STEM education and employment can be divided into two categories: personal and cultural barriers, as well as structural and systemic barriers, as shown in the graph below (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Barriers to women’s participation in STEM in ASEAN

Source: ASEAN-USAID IGNITE Project

Another aspect that influences women’s participation is the opportunity to access leadership roles. This is especially important, as energy transition affects everyone, women and men. Women’s participation in leadership can strengthen inclusivity under the ‘just and inclusive’ principles. In over 20 years, countries in ASEAN have made notable progress in advancing women’s participation in their governance. In 2022, ASEAN women’s representation in management is at 41%, where the middle and senior levels is at 26%. Compared to 2002, women’s participation in government slightly rose to 22% in 2022, showing a positive trend within 10 years.

However, women in high-level decision-making positions, such as at the ministerial level, are more likely to only chair gender-related committee than others like defence, foreign affairs, and energy. This is relevant with existing situation in ASEAN, where all Ministry/Department of Energy in ASEAN Member States are currently led by men. Women at the management level are also more likely to hold positions related only to administration and commerce in sectors such as hospitality and services.

With the income gap, imbalanced responsibility of care, and weak education-to-workforce transitions, it is no surprise that women remain underrepresented in decision-making, especially in the energy sector.

The gender gap in ASEAN’s energy sector does not exist in isolation, it is the result from many different intersecting social structures that constrain women’s agency and limit their full participation. Bridging the existing gap is crucial, as climate change and clean energy transition will impact every segment of society, and unless these challenges are met with inclusive solutions, existing inequalities will only deepen.

The inclusion of more women in technical and leadership roles is not optional, it is vital. To meet the projected , ASEAN cannot afford to overlook half of its talent pool. Women must be equipped, empowered, and enabled to lead in this transition.

ASEAN has demonstrated its recognition of this issue through both regional and global commitments. All Member States have ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), affirming gender equality as a fundamental human right. This marked a critical starting point for the region’s journey towards gender equality. Since then, ASEAN has initiated multiple working groups, policy frameworks, and high-level meetings aimed at promoting women’s empowerment.

In the energy sector, ASEAN has also begun integrating gender considerations into its long-term vision, notably by framing the upcoming ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation (APAEC) 2026–2030 under the theme of a just and inclusive energy transition. This marks a promising step forward, although more must be done.

At the national level, gender-related responsibilities remain largely siloed within Ministries of Women, with limited coordination across technical or infrastructure portfolios. This fragmented approach has left a critical gap: the absence of dedicated institutions or mechanisms that directly address the nexus of gender and energy. Without targeted, cross-sectoral strategies, gender equity efforts risk being side-lined in key areas of policy and investment.

While ASEAN Member States have opened the space for dialogue, this must now translate into integrated action. Recognising the intersectional barriers, particularly across labour, education, and leadership is essential. Only through confronting these structural and cultural obstacles head-on can ASEAN advance gender equality and ensure that the energy transition truly serves all.

Nathania Azalia is a Research Assistant of ASEAN Climate Change and Energy Project (ACCEPT) Phase II and Indira Pradnyaswari is a Research Analyst of ACCEPT Phase II at ASEAN Centre for Energy.

The views, opinions, and information expressed in this article were compiled from sources believed to be reliable for information and sharing purposes only, and are solely those of the writer/s. They do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE) or the ASEAN Member States. Any use of this article’s content should be by ACE’s permission.